Why we care about privacy

Five Lessons from Meta

At NotePass, we are a team of veteran Meta engineers. While we all spent a significant part of our careers working on privacy, we also did so at a company that doesn’t have a great reputation at that, to say the least.

In the 2010s we handed over all of our data to Meta and Big Tech. That was a mistake. But it wasn’t just a mistake for us, it was a mistake for Meta to pursue the strategy.

Once lost, trust is incredibly difficult to regain. Meta tried to innovate its way out of the problem, but to succeed at privacy, it must be a cultural pillar. Meta hid its head in the sand while the number of consumers who demonstrated a care for privacy increased by 4x, the privacy industry matured, and suddenly Meta was at a competitive disadvantage vs its competitors.

We can and should do better for AI. Sign up for NotePass today and experience the peace of mind of end-to-end encrypted Private AI, on any device!

Lesson #1: Once lost, trust is incredibly difficult to regain

“Privacy will just slow you down vs your competition”

“Most people just don’t care about privacy”

“Privacy is just a nice to have”

From 2012-2023 we watched as Meta dealt with consequence after consequence of attitudes like these.

The company made genuine efforts, introduced stringent processes, and took bets on privacy-enhancing technologies that other companies would not, or could not, take, leading to them becoming the technological leader in the space. I myself built a team of 60 engineers that used Multi-Party Computation to enable advertisers to measure their ads performance without sharing any data with Meta. Austin, my co-founder, was a tech lead on the most sophisticated privacy review software in the world.

But ultimately, none of this worked to regain user trust. That’s because trust is a non-renewable resource. Once lost, trust us incredibly difficult to regain, no matter how many privacy features or processes you implement.

Lesson #2: To succeed at privacy it must be a cultural pillar in your company.

I was fortunate to spend a short amount of time at WhatsApp right before end-to-end encryption was first rolled out. WhatsApp offered me a glimpse into a completely different approach.

Conventional product development wisdom at the time was to suck up as much data as you could in your app. WhatsApp turned this on its head, and instead required a strong justification for any metric that was to be collected. Privacy as value was deeply embedded into their culture and every feature was built with privacy by design. To them, introducing end-to-end encryption was a natural next step. Even though it created significant short-term pain, they pushed forward because they felt it was the right thing to do.

Eventually it also proved to be the right product strategy: end-to-end encryption for messaging apps became the industry standard and WhatsApp had the lead. The lesson, which I would only internalize later after years of seeing Meta fail and WhatsApp succeed: to succeed at privacy it must be a cultural pillar in your company.

Lesson #3: Consumer privacy expectations have changed.

Today, for consumer use cases, people generally fall into four categories regarding privacy:

- Privacy Agnostic. People who do not change behavior based on privacy and will accept whatever default is put in front of them. Most people are here.

- Privacy Aware. These people will choose a product that offers more privacy, if equivalent, but their threshold for a behavior change is high. They are often OK with product features and promises to delete data, rather than verifiable guarantees. Product features like Incognito mode or OpenAI Temporary Chats operate here.

- Privacy Driven. These people are educated and will go out of their way to use a more private product. These people tend to use VPNs, Password Managers, privacy-focused browsers, and will go out of their way not share their data with apps.

- Privacy Influencers. Often cryptographers, academics, policy-makers, or people at non-profit organizations dedicated to privacy. They deeply understand the cryptography and privacy tradeoffs behind different solutions and because of that, they hold significant sway over the other groups.

The breakdown of segments can vary across different verticals, such as healthcare and finance, where privacy concerns are more pronounced.

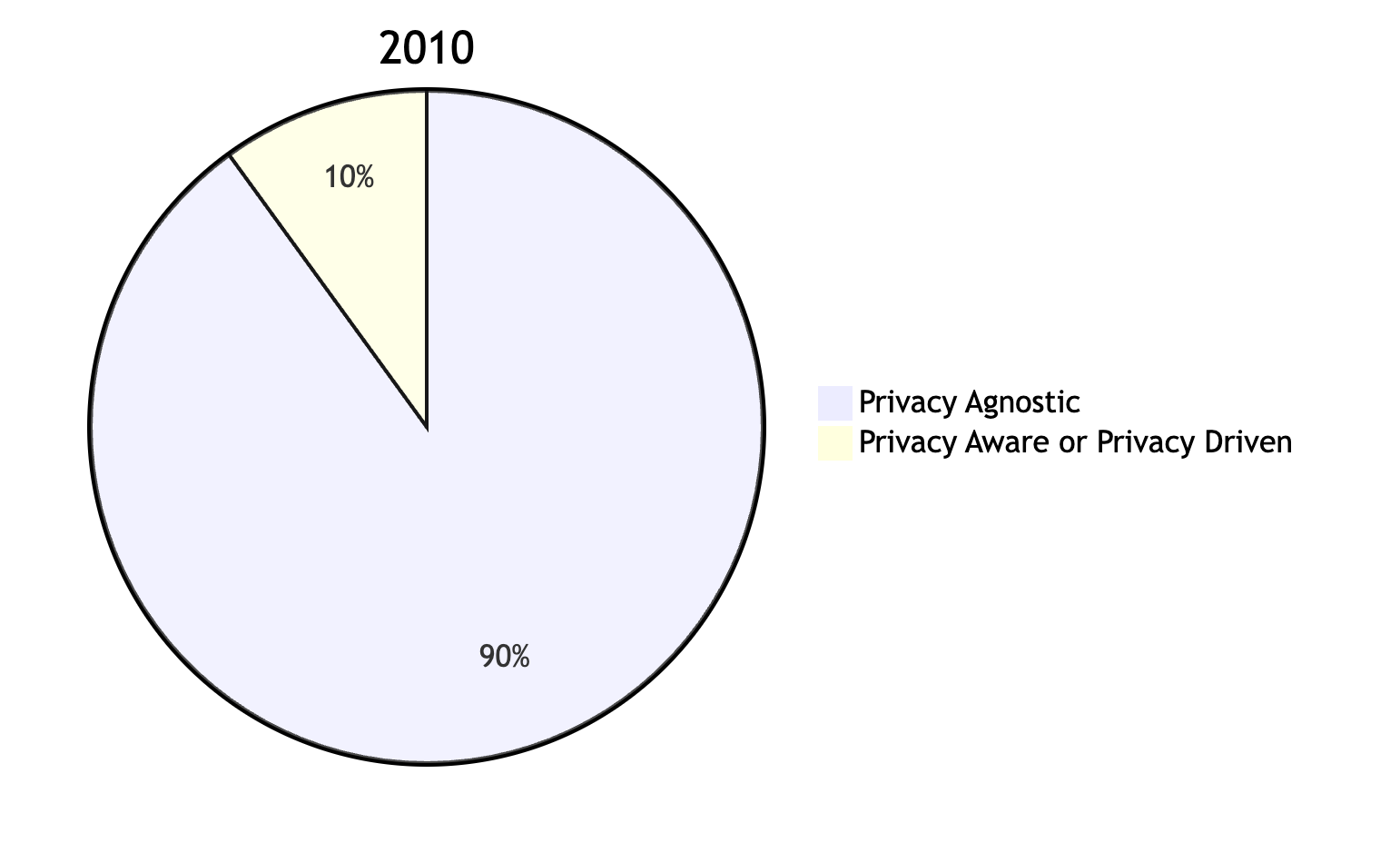

Here’s roughly what this chart would have looked like in 2010.

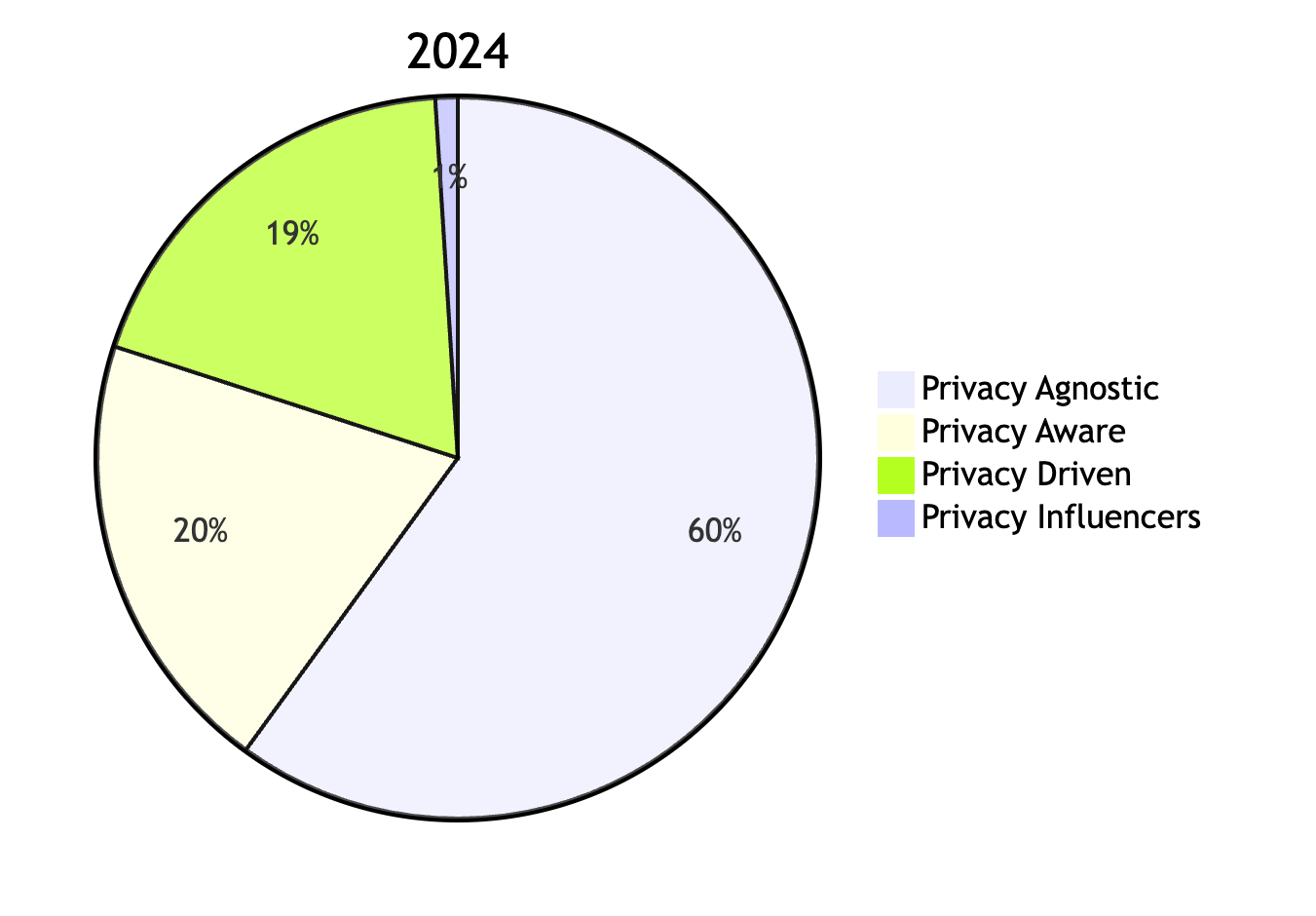

And here is what it roughly looks like today.

At Meta, I watched as the percentage of people who make behavioral changes for privacy steadily crept up. Today, that’s roughly 40% of consumers, up 4x since 2010. Here’s what happened:

- Companies became powerful on the backs of monetizing consumers data

- Countless security breaches made people feel they had lost control of their data

- Internet privacy developed as a field and influencers became a thing.

Eventually, this sentiment reached critical mass and a backlash ensued. We now see wave after wave of regulations, browser policies, and operating system changes to increase consumer privacy, reflecting that consumer privacy expectations have changed. We must build for that world.

Lesson #4: Building for privacy isn’t as expensive as it used to be

Another criticism often levied against focusing on privacy is that you’ll move slower than your competitors, who can move unimpeded without the operational cost of building for privacy.

This is somewhat true. Building for privacy is complex and often requires involvement from security, attorneys, cryptography, and infrastructure experts. These people are hard to find! And because there is often a performance tradeoff in privacy, systems have historically tended to be built in a bespoke way to satisfy the privacy and product requirements of a given solution and no more. These systems are highly efficient but are very difficult to change, often re-involving experts from all of those domains.

Something has changed though: the underlying technology in privacy has evolved to the point where if you design your system well, your ongoing cost is minimal. That’s because there has been a proliferation of generic privacy enhancing technology (PET) frameworks, services, and a dramatic decrease in the cost of high-performance compute.

You still need to have the privacy, security, cryptography, and infrastructure expertise, and just building the technology alone isn’t enough (lesson #1), but if you can satisfy those requirements, you can combine different PETs to create a complex privacy-protecting system with operational flexibility. Building for privacy isn’t as expensive as it used to be.

Lesson #5: Privacy is a powerful competitive advantage

There is a meme that you cannot build a business off of privacy. The market is not large enough, and so it is better to build these organizations as non-profits.

First, as I established in lesson #3, ~40% of consumers demonstrate some kind of care about privacy! But a concrete counterexample in one of the most valuable companies in the world: Apple. Apple’s sole value proposition is not privacy, but it is a foundational cultural pillar in the company for reasons beyond fundamental belief: if you are in a crowded market, privacy is a powerful competitive advantage.

Here’s why:

- Your competitors can’t catch up because privacy is hard. It can’t be bolted on later (lesson #1), adopting it as cultural pillar is not easy (lesson #2), and building for privacy is hard (lesson #4). It historically has required engaging cryptographers, which are even more rare than AI researchers.

- Privacy gives you operational flexibility. We’ve recently seen how Apple has spent years building up its privacy reputation such that it has users’ trust to index their phones for AI, the same thing that Microsoft was scorned for doing with Recall.

- It is a customer acquisition tool and churn reducer. The number of people who want to support a brand that they believe is looking out for their interests is ever-increasing (lesson #4).